Superheroes wanted is the summary appearing on the cover of the May issue of Style Magazine, on newsstands from 27 April 2022 with Corriere della Sera, telling of the need for someone who magically arrives to solve problems. Those many and complex problems that appear day after day in these confused and imprecise times.

Photographed by Mattia Zoppellaro with styling by Alessandro Calascibetta who also interviewed him, Borghi is the protagonist of Diavoli 2. We will then see him in The Hanging Sun, Delta and The eight mountains, Italian and international productions that make him one of the Italian actors mostly in the limelight today. He believes we can all be superheroes if we rid ourselves of prejudice.

WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR SUPER HEROES?

Andrea Rossi, also intervening on the subject in his article Waiting for a new Godot, wonders what happened to the superheroes. And above all who they are. “My superhero has no face or nationality, ignores borders and flags, not to mention sacred places (…). My superhero is an ideal of brotherhood, freedom and solidarity,” he writes. As a superhero of our times he proposes anyone who manages to bring the tensions of everyday life to a rational level.

As does Matteo Rastelli, activist and content creator who, from his Instagram account @rastelling, leads a daily battle for the affirmation of people’s rights. In the article The hoax of lobbies (gay and non-), he takes stock of the online and offline activities of all the institutional and popular initiatives concerning the topic.

FASHION, A QUESTION OF IRONY

For fashion, instead, with the photos of Letizia Ragno, Luca Roscini signs a story of Ironie Formali (Formal Irony). Establishing surprise dialogues between classic suits, regimental ties, cufflinked shirts and lace-up shoes with elements of American football. Francesco Costa recounts the most popular sport in the US in What an incredible mess: American football and how to love it.

Back to fashion with Visioni, in which Michele Ciavarella tells the story of the Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mytos, Muse exhibition taking place at Lacma in Los Angeles until 9 October. The exhibition compares 70 dresses by the great creative, who died prematurely at the age of 41 in 2010, with 200 works of art that served as inspiration.

In Mensfashion, Ciavarella also talks about the construction of a wardrobe with the colors of the Rainbow Flag, the flag of Peace, with jackets, shirts, anoraks in vital colors. Still about fashion, but from an economic aspect, the intervention of Daniela Manca. With fast fashion costing too much for the environment, the deputy director of Corriere della Sera underlines the urgency to promote a culture of reuse and recycling. To encourage a new circular economy.

ART, INQUIRY AND REFLECTION

Giulio Paolini is the artist to whom Martina Corgnati dedicates her article First the work then the artist. Paolini is among the protagonists of the exhibition When is the present at the Museo del Novecento in Florence, inspired by a sentence from a letter from Rainer Maria Rilke to Lou-Andreas Salomé, which said: “The time of art is not measurable. Or rather, it can be identified, sighted, evaluated. But in the intimacy of time it is inexhaustible and eternal “. Here, Corgnati focalizes on the value of Paolini who has always placed creation before himself as an artist.

Enrico Mattei, president of Eni, had also put general interests before particular ones. But, as Andrea Purgatori recounts in The far-sighted freedom of political cinema, his far-sightedness that would have made Italy autonomous for energy needs (gas, above all) was blocked by an attack that blew up the plane he was travelling on. It was October 27, 1962. The story was told in Francesco Rosi’s film The Mattei case which came out ten years later, in 1972. Reconstructing a story on which there is still no official ending. Even today, Putin’s war against Ukraine has made us rediscover the importance of gas supplies.

RESEARCH

AND CREATIVITY

That is, Satyendra Pakhalé’s design manifesto,

according to which “good design is about change, improvement,

the ability to see new possibilities and make them real ».

FROM industrial DESIGN to limited editions, such as his iconic sitting BM Horse, a totemic seamless bronze casting, presented for the first time by the German ammann //gallery at Design Miami / Basel in 2007, after seven years of research. But also devices such as MVC: a modular vaccine carrier to ensure the cold chain in remote localities. A project started in 2006 by industrial designer and architect Satyendra Pakhalé, during his tenure as Head of the Master in Design for Humanities and Sustainable Living at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, Holland, in collaboration with Medici Without Borders and WHO. Or, again, the ergonomic Moonbike with its futuristic traits, created at the invitation of Alicia Framis, multidisciplinary artist and founder of the Moon Life Foundation, a stimulus for designers, artists and architects to create futuristic, realistic and radical concepts for habitat design in an extreme lunar environment. Or,

again: architecture, where the built is not only a sculptural sign but also a relational vector. And so on. Born in 1967 in India, trained in his native country and then in Switzerland, after working for the Dutch Philips on the interiors of a hyper-technological Renault car prototype, Satyendra Pakhalé has been working globally since opening his studio in Amsterdam in 1998, driven by a strong intellectual curiosity which always leads him to go beyond binomials such as high-tech and low-tech, industrial manufacturing and traditional craftsmanship, functions and poetic meaning. Today, with his works in the permanent collections of prestigious museums around the world, from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London to the Pompidou Center in Paris, to draw a trajectory of his research is a volume of over 400 pages: Satyendra Pakhalé Culture of Creation, the result of three years’ work. The fil rouge of this first complete monograph published by nai010 Publishers is already in the title: “Culture of creation” to be understood as the design manifesto of a committed designer to emphasize the ancient and innate impulse of human creation – the human need to create, design, realize, build and turn something into reality. Because, as Satyendra Pakhalé claims, «design is a source of knowledge, even when it remains hidden. It can serve as a basis for the way we live, if it is created with a deep understanding of the value of life. In its most refined form, it can even create joy. Good design is about change, improvement, the ability to see new possibilities and make them real ».

«Design is a source of knowledge, even when it remains hidden. In its finest form it can even create joy “

THE BOOK ILLUSTRATES the whole corpus of works over the last two decades, covering a wide range of topics always addressed with a new perspective, noting the role of design in promoting common good, what Pakhalé defines design for social cohesion. Each project opens up to a multitude of readings. This is the case of Kangeri Nomadic Radiator, finely crafted in aluminum and oak wood, designed for Tubes Radiators. If the name takes inspiration from the kanger, a personal warmer used for centuries by the nomads of northern India, technology offers an alternative response to energy-savings strategies. Or, changing the scale, at the DR. Ambedkar National Center for Social Justice of New Delhi the horizontal bands have the symbolic intent of bringing together different functions (from research activities to those of entertainment) and are designed to protect against glare of the sun, encourage the passage of the air, facilitating the age-old practice of collecting rainwater for passive and evaporative cooling. In all projects, complexity is resolved through experimentation e transformed into elegance, pushing the limits of technology and materials as confirmed by the hamstring plate system DO2-3000 TBI, accomodating the three-dimensional contours of the femur, at the same time satisfying all aesthetics and functionality requirements.

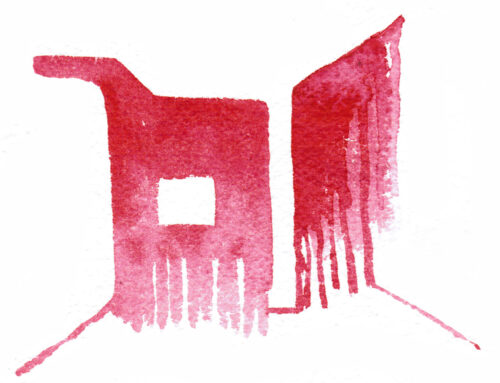

To reveal this “behind the scenes” view of this modus operandi is the editor Jane Szita who, in her essay published in the volume, she confides: «Pakhalé is constantly drawing, using any material within reach, with his favourite Apsara graphite pencil 6B or the watercolor kit he made for himself. The study archives contain several portraits elaborated in pen and ink, as well as other studies carried out on placemats and restaurant paper napkins. Pakhalé began drawing as a child and never stopped. When he opened his studio he started the daily practice of painting a watercolor on hand-made cotton paper, using only one brush. Within these self-imposed limits – basic tools, paper sized 12.5×17.5 cm and a single cut-down brush – the idea was and is to focus on the practice of “thinking through abstraction”>>.

That is to think how a sign can become meaning.

Image title BM Horse:

Result of seven years of research, BM Horse (in the page opposite) is a seamless bronze casting; the unique and innovative process combines different materials to make the piece a truly limited edition.

Image title NEKA:

Opposite page: NEKA-Non Electric Kitchen Appliances is a collection that revisits kitchen utensils in a set of three: blender, whisk and mixer. The challenge: to transform the pleasure of cooking into a sensory experience. Top: Pakhalé.

LA MODA, UNA QUESTIONE DI IRONIA

Per la moda, invece, con le foto di Letizia Ragno, Luca Roscini firma un racconto di Ironie Formali. Stabilendo dei dialoghi a sorpresa tra abiti classici, cravatte regimental, camicie con i gemelli ai polsi e scarpe stringate con gli elementi del football americano. Lo sport più diffuso negli Usa che Francesco Costa racconta in Che incredibile baracconata: l’american football e come amarlo.

Si torna alla moda con Visioni, in cui Michele Ciavarella racconta il percorso della mostra Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mytos, Muse che fino al 9 ottobre si svolge al Lacma di Los Angeles. L’esibizione mette a confronto 70 abiti del grande creativo, scomparso prematuramente a 41 anni nel 2010, con 200 opere d’arte che gli sono servite da ispirazione.

In Mensfashion, sempre Ciavarella racconta la costruzione di un guardaroba con i colori della Rainbow Flag, la bandiera della Pace, con giacche, camicie, anorak in colori vitamici. Ancora alla moda, ma al suo aspetto economico, è dedicato l’intervento di Daniela Manca. Con Il fast fashion costa troppo all’ambiente, il vice direttore del Corriere della Sera sottolinea l’urgenza di promuovere una cultura del riuso e del riciclo. Per incentivare una nuova economia circolare.

L’ARTE, L’INCHIESTA E LA RIFLESSIONE

Giulio Paolini è l’artista a cui Martina Corgnati dedica l’articolo Prima l’opera poi l’artista. Paolini è tra i protagonisti della mostra Quando è il presente?. Al Museo del Novecento di Firenze, nasce da una frase di una lettera che Rainer Maria Rilke inviò a Lou-Andreas Salomé. E che dice: «Il tempo dell’arte non è misurabile. O meglio, lo si può identificare, avvistare, valutare. Ma nell’intimità del tempo è inesauribile ed eterno». Da qui, Corgnati fa discendere il valore di Paolini che ha sempre anteposto la creazione a se stesso come artista.

Anche Enrico Mattei, presidente dell’Eni, aveva anteposto gli interessi generali a quelli particolari. Ma, come racconta Andrea Purgatori in La libertà lungimirante del cinema politico, la sua lungimiranza che avrebbe resa autonoma l’Italia per il fabbisogno energetico (gas, soprattutto) fu bloccata da un attentato che fece scoppiare l’aereo che lo trasportava. Era il 27 ottobre del 1962. La storia venne raccontata dal film di Francesco Rosi Il caso Mattei che uscì sugli schermi dieci anni dopo, nel 1972. Ricostruendo una vicenda sulla quale non c’è ancora la parola fine ufficiale. Ancora oggi che la guerra di Putin contro l’Ucraina ci ha fatto riscoprire l’importanza dell’approvvigionamento del gas.

RICERCA

E CREATIVITÀ

Ovvero, il manifesto progettuale di Satyendra Pakhalé,

secondo il quale «il buon design riguarda il cambiamento, il miglioramento, la capacità di vedere nuove possibilità e renderle reali».

DAL DESIGN industriale alle edizioni limitate, come l’iconica seduta BM Horse, un

oggetto totemico fuso in bronzo senza saldatura presentato per la prima volta alla tedesca ammann//gallery a Design Miami/Basel nel 2007, dopo sette anni di ricerca. Ma anche dispositivi come MVC: un vettore di vaccini modulare per garantire la catena del freddo in località remote. Un progetto avviato nel 2006 dal designer industriale e architetto Satyendra Pakhalé, durante il suo incarico a capo del Master in Design for Humanities and Sustainable Living alla Design Academy di Eindhoven, in Olanda, in collaborazione con Medici Senza Frontiere e OMS. O, ancora, l’ergonomica Moonbike dal tratto futuribile, creata su invito di Alicia Framis, artista multidisciplinare e fondatrice

della Moon Life Foundation, uno stimolo per designer, artisti e architetti a creare concetti futuristici, realistici e radicali per la progettazione di habitat in un ambiente lunare estremo. O, ancora: l’architettura, dove il costruito non è solo segno scultoreo ma anche vettore relazionale. E molto altro. Nato nel 1967 in India, formatosi nel suo Paese natale e poi in Svizzera, dopo avere lavorato per la Philips olandese sugli interni di un ipertecnologico prototipo di auto Renault, Satyendra Pakhalé lavora a livello globale dal suo studio ad Amsterdam dal 1998, spinto da una forte curiosità intellettuale, che lo porta sempre ad andare oltre a binomi come high-tech e low-tech, produzione industriale e artigianato tradizionale, funzione e significato poetico. Oggi che i suoi lavori sono nelle collezioni permanenti di prestigiosi musei di tutto il mondo, dal Victoria and Albert Museum di Londra al Centre Pompidou di Parigi, a tracciare una

traiettoria della sua attività di ricerca è un volume di oltre 400 pagine: Satyendra

Pakhalé Culture of Creation, risultato di tre anni di lavoro. Il filo rosso di questa prima monografia completa pubblicata da nai010 Publishers è già nel titolo: «Cultura della creazione» da intendersi come il manifesto progettuale di un designer impegnato a

rimarcare l’antico e innato impulso alla base della creazione umana. Ovvero il bisogno umano di creare, progettare, realizzare, costruire e portare qualcosa nella realtà. Perché, come afferma Satyendra Pakhalé, «il design è una fonte di conoscenza, anche quando rimane nascosta. Può servire come base per il modo in cui viviamo, se è creato

con una profonda comprensione del valore della vita. Nella sua forma più raffinata, può persino creare gioia. Il buon design riguarda il cambiamento, il miglioramento, la capacità di vedere nuove possibilità e renderle reali».

«Il design è una fonte di conoscenza, anche quando rimane nascosta. Nella sua forma più raffinata può persino creare gioia»

IL LIBRO ILLUSTRA l’intero corpus di opere nel corso degli ultimi due decenni, coprendo un’ampia gamma di argomenti affrontati sempre con una nuova prospettiva, rimarcando il ruolo del design nella promozione del bene comune, quello che Pakhalé definisce design per la coesione sociale. Ogni progetto apre a una moltitudine

di letture. È il caso di Kangeri Nomadic Radiator, il radiatore portatile in alluminio e legno di quercia finemente lavorato a mano, progettato per Tubes Radiatori. Se il nome prende ispirazione dai kanger, gli scaldini personali usati per secoli dai nomadi dell’India

settentrionale, la tecnologia offre una risposta alternativa alle strategie di risparmio

energetico. O, cambiando scala, il DR. Ambedkar National Centre for Social Justice di Nuova Delhi, dove le bande orizzontali che «fasciano» l’edificio con l’intento simbolico di riunire diverse funzioni (dalle attività di ricerca a quelle di intrattenimento) sono

progettate per proteggere dal riverbero del sole, incoraggiare il passaggio dell’aria facilitando la pratica secolare della raccolta dell’acqua piovana per il raffreddamento passivo e evaporativo. In tutti i progetti, la complessità viene risolta attraverso la sperimentazione e trasformata in eleganza, spingendo i limiti della tecnologia e dei materiali come conferma il sistema di placche femorali TBI DO2-3000, progettato

tenendo conto dei contorni tridimensionali del femore, soddisfacendo al tempo stesso estetica e requisiti di funzionalità. A svelare un dietro le quinte di questo modus operandi è l’editor Jane Szita che, nel suo saggio pubblicato nel volume, confida: «Pakhalé disegna costantemente, utilizzando qualsiasi materiale abbia a portata di

mano, con la sua matita di grafite Apsara 6B preferita o il kit di acquerelli che ha realizzato lui stesso per sé. Gli archivi dello studio contengono diversi ritratti elaborati a penna e inchiostro, nonché altri studi realizzati su tovagliette e tovaglioli di carta da ristorante. Pakhalé ha iniziato a disegnare da bambino e non ha mai smesso. Quando

ha aperto il suo studio ha iniziato la pratica quotidiana di dipingere un acquerello su carta di cotone fatta a mano, usando un solo pennello. Entro questi limiti autoimposti – strumenti di base, un formato carta di 12,5×17,5 cm e un unico pennello troncato – l’idea è quella di concentrarsi sulla pratica del “pensare attraverso l’astrazione” ». Ovvero pensare come un segno possa diventare un significato.