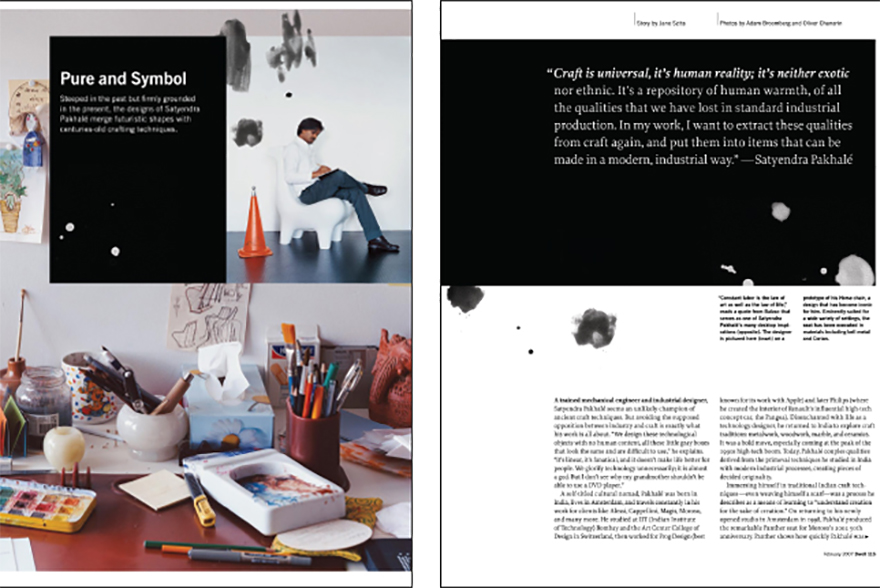

A trained mechanical engineer and industrial designer, Satyendra Pakhalé seems an unlikely champion of ancient craft techniques. But avoiding the supposed opposition between industry and craft is exactly what his work is all about. “We design these technological objects with no human content, all these little gray boxes that look the same and are difficult to use,” he explains. “It’s linear, it’s fanatical, and it doesn’t make life better for people. We glorify technology unnecessarily; it is almost a god. But I don’t see why my grandmother shouldn’t be able to use a DVD player.”

A self-titled cultural nomad, Pakhalé was born in India, lives in Amsterdam, and travels constantly in his work for clients like Alessi, Cappellini, Magis, Moroso, and many more. He studied at IIT (Indian Institute of Technology) Bombay and the Art Center College of Design in Switzerland, then worked for Frog Design (best known for its work with Apple) and later Philips (where he created the interior of Renault’s influential high-tech concept car, the Pangea). Disenchanted with life as a technology designer, he returned to India to explore craft traditions: metalwork, woodwork, marble, and ceramics. It was a bold move, especially coming at the peak of the 1990s high-tech boom. Today, Pakhalé couples qualities derived from the primeval techniques he studied in India with modern industrial processes, creating pieces of decided originality.

Immersing himself in traditional Indian craft techniques—even weaving himself a scarf—was a process he describes as a means of learning to “understand creation for the sake of creation.” On returning to his newly opened studio in Amsterdam in 1998, Pakhalé produced the remarkable Panther seat for Moroso’s 2002 50th anniversary. Panther shows how quickly Pakhalé was able to devise a new design vocabulary, consisting of a kind of functional sculptural engineering coupled with a poetic shorthand of form. A zoomorphic shape, embodying an essential animalist quality, creates a sophisticated effect through a hieroglyphic simplicity. Functionally, it’s an incredibly versatile piece of furniture for sitting (the word “chair” seems a wholly inadequate description here); aesthetically, Pakhalé notes that people are often taken aback by the ambiguity of Panther’s form, and have to ask how to sit on it—although, he adds, “kids don’t have to be told, they instinctively see the possibilities.

Panther was followed by the elegant Fish chair for Cappellini, the slender Bird chaise, and the iconic Horse chair. In this series, Pakhalé conjures a whole bestiary of symbolic forms. “In industrial culture, we have lost symbology and things don’t mean anything anymore,” he explains. “I am trying to bring this back, almost in the form of an algebraic language.” The symbolic language he uses, with its expression of what he sees as the essential qualities of birds and fish, is coupled with the use of craft techniques that he has exhaustively researched so as to transform them into industrial processes allowing for mass, or at least serial, production.

The combination lends his work a remarkable ambiguity: It appears both archaic and futuristic. Take Pakhalé’s extraordinary ceramic designs, the Roll and Flower Offering chairs, which suggest nothing so much as archaeological artifacts from an alien planet. Ceramic was an obvious choice for a designer with a taste for paradox to explore: “I wanted to make ceramic chairs because chairs aren’t ever ceramic,” he says. “So first I found some ceramicists and we experimented with hand-thrown shapes—they hated this because of the nostalgia aspect, but it doesn’t affect me that way.” This traditional technique produced volumes that Pakhalé used to create a prototype. “When I was ready to put it into production, we found a mold maker near Venice who could make the molds. The elements had to be cast separately, and we developed a special joint to connect the pieces, which were then glued together using a polyurethane glue used in space technology.” The final pieces are evidence that the manufacturing process is always intrinsic to the development of the object in Pakhalé’s work.

Now that so much design looks as if it has sprung directly from a computer, and probably has, Pakhalé’s work makes a particularly powerful statement. “No software can do this,” he says of his Akasma glass baskets—deceptively simple-looking objects that nevertheless require the manipulation of laser jets, heating, and hand-bending to achieve their elegant parallel lines. As the designer puts it, the process is “craft, complete with all the modern technology. Humans are all about touch and feel,” he says simply. “This is what we’ve lost through industrialization. This is what led me to go back to basics. Craft is universal, it’s human reality, it’s not exotic or ethnic. But on the other hand, I don’t want to sit in the corner casting metal—I want to make things in a modern way.”

Clearly, Pakhalé wants to bring crafts back into everyday design. “It’s not from nostalgia for the past that I study crafts, because I don’t have that adoration of handmade things,” he explains. “I’d rather not have to see my thumbprints in the things I make. It was more as an antidote to industrial culture, a reality check, that I went back to India to look at crafts. I want to recapture that basic feeling, the way children in the act of drawing are so in tune with themselves, the way that craft allows you to explore the sensory quality of materials.”

Read the full article on dwell