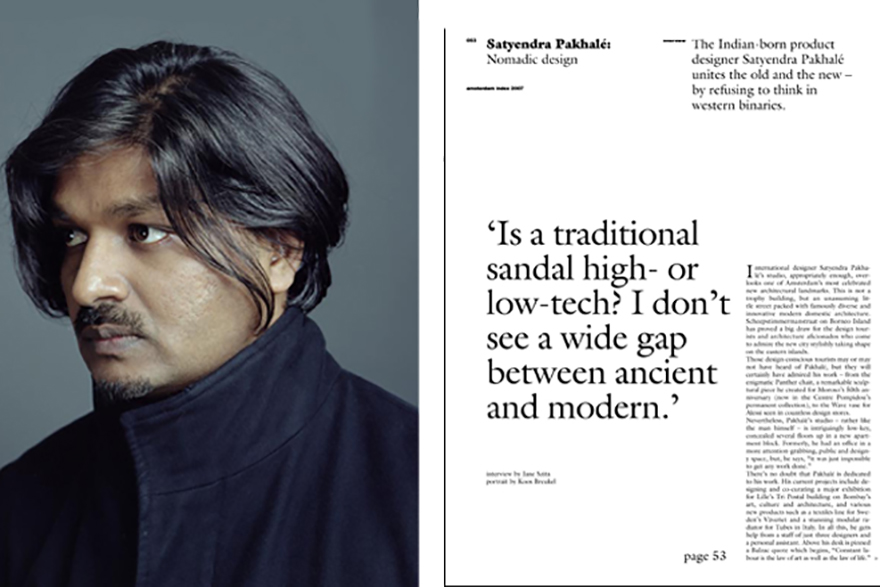

The Indian-born product designer Satyendra Pakhalé unites the old and the new – by refusing to think in western binaries.

‘Is a traditional sandal high- or low-tech? I don’t see a wide gap between ancient and modern.’

International designer Satyendra Pakhalé’s studio, appropriately enough, overlooks one of Amsterdam’s most celebrated new architectural landmarks. This is not a trophy building, but an unassuming little street packed with famously diverse and innovative modern domestic architecture. Scheepstimmermanstraat on Borneo Island has proved a big draw for the design tourists and architecture aficionados who come to admire the new city stylishly taking shape on the eastern islands.

Those design-conscious tourists may or may not have heard of Pakhalé, but they will certainly have admired his work – from the enigmatic Panther chair, a remarkable sculptural piece he created for Moroso’s 50th anniversary (now in the Centre Pompidou’s permanent collection), to the Wave vase for Alessi seen in countless design stores. Nevertheless, Pakhalé’s studio – rather like the man himself – is intriguingly low-key, concealed several floors up in a new apartment block. Formerly, he had an office in a more attention-grabbing, public and designy space, but, he says, “it was just impossible to get any work done.”

There’s no doubt that Pakhalé is dedicated to his work. His current projects include designing and co-curating a major exhibition for Lille’s Tri Postal building on Bombay’s art, culture and architecture, and various new products such as a textiles line for Sweden’s Väveriet and a stunning modular radiator for Tubes in Italy. In all this, he gets help from a staff of just three designers and a personal assistant. Above his desk is pinned a Balzac quote which begins, “Constant labour is the law of art as well as the law of life.”

‘Technology all looks the same; there’s no human content. This is the fault of the design.’

As Pakhalé puts it himself, “Design is not a profession, but a way of life.” He now spends much of his time travelling to stay inspired and informed and to visit clients around Europe (only one, Cor Unum, is Dutch). That leaves him little time to daydream over the evocative view from his office window – the old dockland landscape that for centuries connected Amsterdam with the world and all it had to offer in terms of trade. The docks were, perhaps, the original multicultural melting pot, and the Indian-born international designer’s presence here today seems entirely appropriate.

From Frog to Panther ~ It’s all a long way from the small town in central India where Pakhalé was born. His family were neither craftsmen nor designers, but they encouraged him in his early love of making things. “What I do now is not so different from what I was doing when I was a kid,” he says. “It’s about simplifying situations, although not in a simplistic way.”

Yet the intuitive creative process Pakhalé aspires to now – whose results are clear in the playful yet ruthlessly economical forms of furniture pieces like the Bird chaise, or the Fish chair for Cappellini – emerged only after a struggle to escape an earlier life as a high- tech designer during the dot-com boom. Following an industrial training (IIT in Bombay, then the Swiss Art Centre College of Design), Pakhalé joined Frog, the design company famous for its work with Apple. He then turned down a number of offers to work in California’s Silicon Valley (even then, he was wary of its technological monoculture) in favour of Dutch giant Philips. There, he created the interior of the influential Pangaea concept car for Renault, devising sophisticated communications technology, flat computer screens and other now-familiar elements that didn’t exist in 1996.

“I think we achieved a beautiful integration of technology with the environment,” says Pakhalé, who is equally proud of the interior’s human warmth, achieved with recycled- wood flooring and soft lighting.

Although Philips was “an interesting playground,” Pakhalé became disenchanted with what he saw as the soulless nature of technology design. “In the high-tech world, people talk as if there was no life before the mobile phone,” he says. “Technology is used in such a linear, fanatical way, it doesn’t actually make life any better. All those plastic boxes look the same; there’s no human content. This isn’t the fault of technology but of design.”

So, inspired to “understand creativity for creativity’s sake” and put human content back into his work, Pakhalé left Philips, opened his own studio in Amsterdam, and spent months in India exploring handicrafts. “It wasn’t about rejecting the modern world,” he says, “but about getting back to basics.

I was looking for something universal – something with local roots but that would appeal to people everywhere, like the work of Issey Miyake, which is intrinsically Japanese and yet has this universal appeal.”

He began devoting lots of time to making things by various means, even weaving himself a scarf. “This allowed me to explore the sensory quality of materials,” he says. “Industry is on a one-way track. Just because we use machines to make things, why should that limit us to the same old straight lines, the same old materials? I didn’t want to do a craft for its own sake, out of some kind of nostalgia, however; I was seeking the human quality of design so I could incorporate it into my industrial design.”

Back in Amsterdam, Pakhalé applied his newfound principles to a commission from the Italian company Moroso. Functionally speaking, his Panther seems altogether too complex an object to be called a chair, despite its breathtaking simplicity of line. It has several very different positions for sitting and lounging in a variety of postures. “People always seem rather taken aback by Panther,” says Pakhalé. “Invariably, they ask, ‘But how do I sit in it?’ However, a child doesn’t have to ask. Children immediately see the possibilities.”

Panther, like many of the designer’s pieces, almost seems to resist categorization as an inanimate object. In name and form, it has a zoomorphic reference: what Pakhalé calls a totemic quality. “In industrial culture, we have lost symbology, and things don’t mean anything anymore,” he explains. “I am try- ing to bring this back, almost in the form of an algebraic language. That doesn’t mean using animal symbols and so on in a representational way, but in an abstracted way. I want to convey the essence of form.”

Beyond high- and low-tech ~ Despite its naive nuances, Panther, like all Pakhalé’s work, has a sculptural quality that demonstrates a sophisticated preoccupation with engineering and technique. It’s as though he takes a low-tech formulaic language recognizable from children’s drawings and tribal art and embodies it in a high-tech manner, through process, materials or both. But the designer finds such polarity reductive: “Is a traditional leather sandal high-tech or low-tech?” he asks. “I really don’t know. I don’t see such a wide gap between ancient and modern. In India, I grew up among ancient things that actually look very contemporary.”

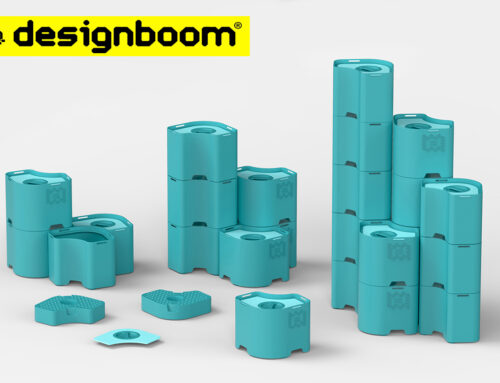

So Pakhalé takes ancient craft techniques – bell metal and ceramics, for example – and industrializes them. “I don’t just want to make one-offs, things with my thumbprints on,” he insists. He used the bell-metal technique, in which wax is coiled around the clay to create a spiral form for metal casting, to create his remarkable BM Horse chair. His BM (bell-metal) baskets and vases led him to translate the process into stereolithography for his STL vase and hanger – laser- made equivalents of the original handcraft technique. Another evolution of the series came with his stainless-steel Wave vases for Alessi, whose rippled surfaces magnify the original spirals in a process of great technical difficulty.

He’s particularly proud of his Akasma glass baskets, whose deceptively simple form required the manipulation of water jets, heating, and hand bending. “This is a craft, complete with all the modern technology,” says Pakhalé. “No software can do this.” The designer, who admits to spending six months on a prototype, is aghast that others don’t bother with models. For him, they’re “the perfect way of testing the human qualities of design.”

The experimental process, it seems, is never over for Pakhalé: the BM Horse has appeared in bell metal, fibreglass, synthetic resin, and Corian, as well as with a flocked surface, and he’s working on a ‘sliced’ version incorporating sections of different materials. Because ceramics are not associated with seating, Pakhalé decided to make ceramic chairs. Now produced from moulds in a factory near Venice and joined using a glue developed in the aerospace industry, the Flower Offering Chair is a purely totemic object, he says – a means of expression, like a song.

Given that he spends large chunks of his time travelling to Italy, Scandinavia, France and the US, why live in Amsterdam? Logistically, of course, it’s ideally positioned to reach just about anywhere. But also, says Pakhalé, “Amsterdam is a city where human values and the human scale are very well expressed. You can walk anywhere.” And it seems he does; he doesn’t own a car – in the Netherlands, anyway. The self-styled cultural nomad slips easily between modern and ancient cultures, east and west, technology and craft, high and low tech. And Amsterdam has always been a place where different cultures seem to coexist, in layers that barely touch. Which must be why Pakhalé clearly thrives here.

‘I was looking for something with local roots that would appeal to people everywhere, like Issey Miyake’s work.’